[W]hen Sarah Kluth is asked about the decaf at Revelator Coffee, she doesn’t hold back, she doesn’t sugarcoat her opinion, or pretend the coffee’s something it’s not. She describes it exactly how she sees it.

“Our decaf cold-brew is dope,” she says.

This sort of enthusiasm for decaf is a rare thing. Until recently, it would have been laughable in most specialty coffee circles. Sure, you might roast or serve decaf, but you didn’t act like it was good. You certainly didn’t hype it. It was decaf, after all, a branch of coffee beset by poor manufacturing practices, high processing costs, slim choices for quality green, and over-roasting—all of which led to pretty crappy decaf over the years.

But Kluth is no novice to coffee, and her claim isn’t mere boosterism. A veteran at Intelligentsia and now the director of coffee production for Revelator Coffee out of Birmingham, Alabama, she has helped the young but rapidly expanding Southern chain shape its line of coffees and procure a dope decaf.

Her stance wasn’t always in favor of decaf. Like many other coffee directors and roasters around the country, she was long a skeptic of the potential for decaf to stand alongside its full-caffeine counterparts. Even now, her take on her decaf doesn’t extend to decaf writ large. “We have decaf because we know we can make it taste good,” says Kluth.

Decaf customers should be your favorites. These are the people who are drinking for flavor, not stimulus.

Decaf has long been an afterthought for many roasters. Some specialty shops refuse to include it on their menus. While decaffeination outfits have improved processing techniques and sourcing practices that sullied the reputation of caffeine-free coffee, overcoming the stigma attached to decaf still scares off many roasters from embracing their decaf customers and developing that segment of business. Rob Hoos, the head roaster at Nossa Familia Coffee in Portland, thinks roasters need to get over it. “Decaf customers should be your favorites,” he says. “These are the people who are drinking for flavor, not stimulus.”

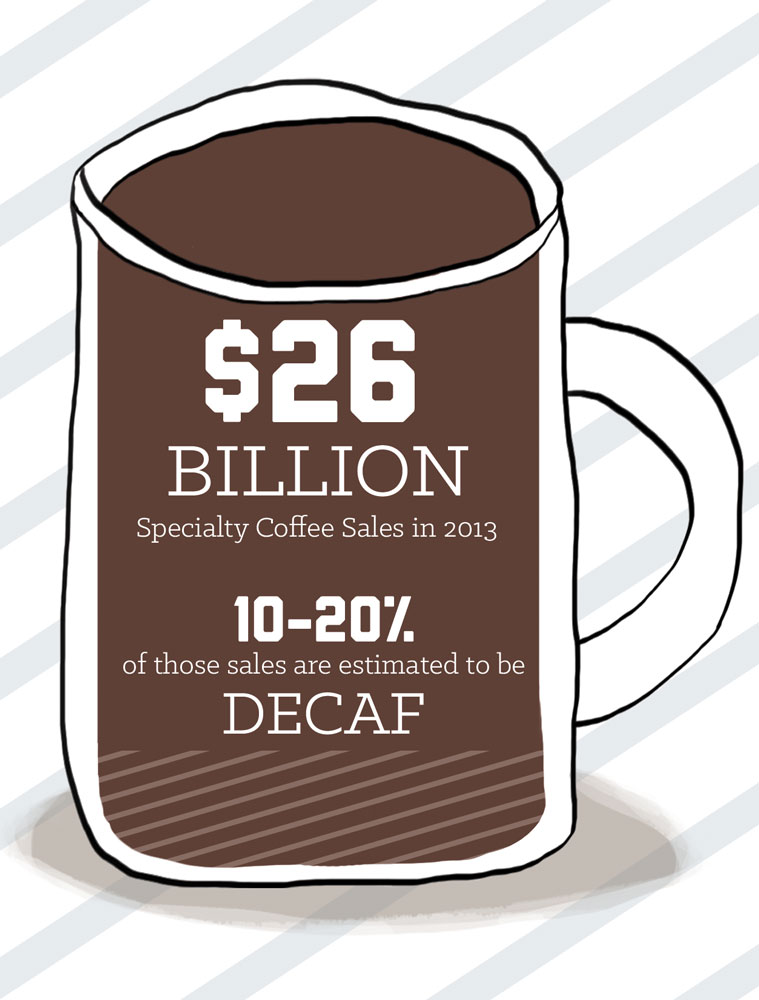

In 2013, the most recent year data is available, the SCAA reported specialty coffee sales in the United States reached nearly $26 billion. Figures for decaf weren’t broken down, and when it comes to coffee market reports, there’s not a lot of solid data for decaf. But companies who know decaf well, such as Swiss Water Decaffeinated Coffee Company, estimate that decaffeinated coffee accounts for 10 to 20 percent of annual coffee sales, depending on the region.

So why, despite its potential for profit, is decaf still struggling to gain traction among specialty coffee professionals?

[K]luth’s own drinking habits show one of the major hurdles. Even after being persuaded decaf could be great, and even though she has it readily at hand, she says she often forgets she can grab a great cup of decaf before she heads home at the end of the day. “I’m even to blame,” says Kluth. “Suddenly we have this coffee worth drinking, but don’t have a consumer pattern to support it.” She describes conversations with customers about the last time they had decaf; for many of them, it’s been over a decade. Considering lingering associations with bad decaf of the past, it’s hard to blame people for a dearth of enthusiasm about the new wave of specialty decaf coffee.

David Kastle is the vice president of trading for Swiss Water and knows all about the horrors of past decaf selections. “Coffee may not have been so great in the fifties and sixties, but the decaf was just awful,” he says.

Historically, issues with quality often began with the beans selected for decaffeination. The decaffeination process substantially increases the coffee’s final price tag, but decaf was sold for the same price as regular coffee. To alleviate the expense, importers and processors traditionally relied on second-rate green coffee that yields second-rate product.

“No one wants to pay more for something that they can’t charge more for,” says Kastle. “The way you mitigate that is you buy a decaf that’s either made with really old coffee or rejected coffee, or you use a really cheap decaffeination process.” He says that for years this was the standard. “That’s what decaf was.”

Luis Demetrio Arandia Muguira is the president of Descamex, a Mexican decaf processor with two plants in Córdoba, Veracruz, that works with customers all over the world. Muguira says that everyone working in the coffee industry has known that better decaf required better beans and a higher price tag. Customers, though, didn’t know.

That could be changing. As the specialty market grows, quality becomes a higher priority at every step of the supply chain and roasters and consumers expect better coffee. They’re also willing to spend more for it, and there’s a growing appetite for more expensive decaf.

The recent success of specialty decaf processors like Swiss Water and Descamex demonstrates that consumers will pay more for quality decaf. Though Swiss Water incorporated in 2000, they’ve seen a 40 percent growth in just the last four years. The growing demand for quality might open opportunities for price adjustments on the retail side, encouraging more roasters and retailers to invest in offering better decaf to customers.

[E]ven when roasters allocate more of their budget to better decaf, they are still often limited by what their importers offer. That’s because economies of scale are critical in decaffeination. Dane Loraas is a relationship coffee manager with importer Sustainable Harvest. He says that optimal batch size for decaffeination is typically one to two containers of green, which equates to about 70,000 pounds of coffee. Such large quantities aren’t conducive to producing highly specialized products. When a unique, small-lot decaf does come across the hands of importers, quantity limitations tend to spike prices. “It’s not a sustainable idea for increasing the quality of decaf,” Loraas says.

Roasters that work directly with decaf processors often have more freedom to select the beans they’d like decaffeinated—whether by choosing from a wider selection of beans available from the processor, or by sending their own greens. Manufacturers like Descamex and Swiss Water have found success in their ability to cater to individual client requests, giving roasters a much higher level of control over the quality of green beans processed for decaf.

Descamex clients determine how decaf beans will be processed; the company operates separate plants for their methyl chloride- and water-based processes. Muguira says that clients in some regions of the world trend toward natural products, but that because of cost there is still a growing demand for methyl-chloride processed decaf.

At Swiss Water, which solely uses its eponymous process, Kastle cites their ability to run relatively small batches as a key to their success.

[G]etting roasters and importers to invest in better quality green beans for all the coffee they produce, not just the caffeinated roasts, is just one of the many challenges keeping decaf from rising to its full potential in the specialty market, especially in America.

Only a handful of decaffeination methods exist and most manufacturers are located outside of the United States. Each method has its appeals, including cost, quality, and means used in the process. Decaf made with methylene chloride or ethyl acetate was the only choice available for many years. While not shown to retain any of the chemicals used in processing, these methods can be a hard sell to customers in a market dominated by buzzwords like natural and organic. The demand for naturally derived foods has helped give rise to water processing methods and Atlantic Coffee Solutions’ carbon dioxide method, both classified as non-solvent based processes because no chemical solvents are used to remove caffeine.

I’ve spent the last couple years trying to explain to roasters that they should stop roasting decaf like it’s anything other than coffee.

“Quality is definitely a major part of the decision,” says Kevin Nealon, a roaster at Denver’s Huckleberry Roasters. Huckleberry uses both Swiss Water and Mountain Water processed decaf coffees, a choice mirrored by many specialty roasters offering better decafs. “I don’t want to suggest that MCl decaf has any major health implications, but water processed coffees are doubt-free, both for us and our customers,” Nealon says.

That sentiment is common among roasters. The desire for natural products, or at the very least products that seem to have minimal processing, has opened the market for specialty decaf and created a significant advantage for companies that use water and carbon dioxide methods.

[K]astle explains that one of his greatest challenges is convincing roasters to view decaf beans in the same light as their caffeinated counterparts. “I’ve spent the last couple years trying to explain to roasters that they should stop roasting decaf like it’s anything other than coffee,” he says. While he acknowledges that slight adjustments may be necessary when roasting decaf, the overall approach should be the same. “If you’re roasting a decaf Guatemala, approach it as a Guatemala coffee.”

For his part, Muguira hopes that better decaf will encourage coffee lovers to indulge all day long without concern. “A good kick in the morning is always great, but afterwards you can drink as many as you like with no worries of how you are going to sleep at night.” That’s a real concern for many coffee drinkers, something caffeine-tolerant coffee pros should keep in mind. Nearly half of coffee drinkers cite concerns about caffeine as a reason for limiting their coffee consumption, according to the 2015 National Coffee Drinking Trends report from the National Coffee Association.

As the population of coffee drinker’s ages and metabolic sensitivity to caffeine increases, Kastle expects the demand for craft decaf to swell. “You’ve got all these people who’ve been drinking better coffee for so long . . . and then you go to just really crap canned decaf,” he says, noting how this abrupt transition has created a wide opening in the market for specialty decaf. Kluth, from Revelator Coffee, also points out that as an industry, many roasters and baristas are still in an age group that doesn’t typically experience adverse effects from caffeine. “As we start to get older, what do we do next?” she says.

The success of craft decaf has been supported in blind taste tests conducted at trade shows, cuppings, and business meetings. Using both regular and decaffeinated beans from the same lots, decaf manufacturers have found decaf roasts that out-perform regular coffee in blind taste tests. Swiss Water and Descamex have both used blind tastings at trade shows to try out their products on industry veterans. “I love to see very talented cuppers having trouble finding out which is the decaf and which is the regular,” Muguira says.

Nearly half of coffee drinkers cite concerns about caffeine as a reason for limiting their coffee consumption.

Hoos describes a similar phenomenon at the cuppings held weekly at Nossa Familia. The decaf often wins taste tests in blind coffee cuppings. Hoos reasons that it’s an easy coffee to like, as it’s sweeter, mild, and lacks some of the unwelcome qualities that more nuanced roasts sometimes display.

A skeptic would point out, rightly, that these are comparisons of different coffees, an apples-to-oranges test that doesn’t tell us if a decaf is as good as a regular coffee from the same lot. Side-by-side comparisons are something Hoos hopes to do in the future. Still, the stereotype of decaf says it should declare itself like a defective coffee. It doesn’t.

In an industry driven by single-origin selections and fair-trade product, the demand for better overall quality has opened the door for craft decaf. As the population of specialty decaf drinkers continues to grow, more roasters will need to answer to these sophisticated palates.

—Ellie Bradley is Fresh Cup‘s associate editor.